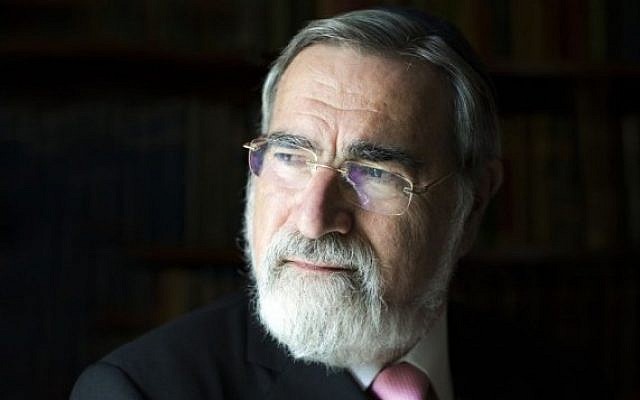

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, the former Chief Rabbi of England, died yesterday at the age of 72.

The world lost a beacon of light in the tumultuous waters of world history that we’re living in.

I did not know Rabbi Sacks personally, but I referred to his teachings weekly when preparing for my classes. When a certain encounter in the weekly Torah portion plagued me, I would often type it into Google to find that Rabbi Sacks had posed the very same question. Before long, I started to go directly to his site for guidance on the weekly Torah portion. Because of his secular background, he often sprinkled in literary comparisons and analogies. Being an English major, I appreciated this. That is not to say that he viewed the Torah as just another academic text. Rather, he could pull from academia to better crystallize the Torah’s meaning.

Let me give you an example that I just read about and discussed with my students this past week in this past Shabbat’s Torah portion, Vayera.

How is it that Abraham could willingly sacrifice his own son? How is it that he went to do this enthusiastically, as we learn that the morning he left to carry out the mission, he was so excited to do G-d’s bidding, he saddled his own donkey? How is this humanly possible?

Rabbi Sacks’ explanation, published last year, helped me to understand what exactly was going on here. Unlike many commentators, he did not believe that Abraham was being asked by G-d to sacrifice his own son, which was a practice utilized by other religions of the day.

The trial was to see whether Abraham could live with what seemed to be a clear contradiction between God’s word now, and God’s word on five previous occasions, promising him children and a covenant that would be continued by Isaac.

Abraham knew that Hashem wouldn’t kill his only son, the one that He had promised would lead to a large nation. But Abraham didn’t know exactly how this promise would play out. Nevertheless, he believed anyway. Rabbi Sacks borrowed the phrase – negative capability, from John Keats, who had used it to describe Shakespeare: “When a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

Rabbi Sacks’ musings on the Parsha were clear, inspirational, well-written and always cut right to the heart of the issue. His ability to weave in secular and literary thinkers into his thoughts on the Torah portion made it much more vivid to me.

I often think about how my father’s Judaism was so impacted by Rabbi Soloveitchik at Yeshiva University and his own rabbi at school, Rabbi Aharon Lichtenstein. Scholars not just of the Torah, but of academia as well. It is this lens of Torah that helps me make sense of the Torah portion again and again, when it often does not make sense to my simple, questioning self.

Just like Abraham exhibited faith in times of uncertainty in this week’s Torah portion, so did Rabbi Sacks.

It was his faith that I read about just a few short weeks ago, when the world learned that he was facing cancer yet again, after two private battles with the disease during his lifetime.

In a 2013 interview with Tablet magazine, he explains why he never publicized his battles with cancer in his writings.

“It’s very simple,” he said. “I saw my late father in his 80s go through four, five major operations. This was not cancer, it was hip replacements and those things. And when you have operations in your 80s, they sap your strength. He got weaker and weaker as the decade passed. He was walking on crutches at my induction—he was alive for my induction, and that was very important to me.”

“Now, my late father, alav ha-shalom, didn’t have much Jewish education, but he had enormous emunah [faith],” Sacks continued. “I used to watch him saying Tehillim in the hospital, and I could see him getting stronger. It seemed to me that his mental attitude was ‘I’m leaving this to Hashem. If he sees that it’s time for me to go, then it’s time for me to go. And if he still needs me to do things here, he’ll look after me.’”

“And I adopted exactly that attitude. So on both occasions I felt, if this is the time Hashem needs me up there, thank you very much indeed for my time down here; I’ve enjoyed every day and feel very blessed. And if he wants me to stay and there’s still work for me to do, then he is going to be part of the refu’ah [healing] and I put my trust in him. So there was no test of faith at any point—just these simple moments at which to say, ‘b’yado afkid ruchi’ [‘In his hand, I place my soul’]. That was my thought. And since we say that every day in Adon Olam, I didn’t feel the need to write a book about it. It was for me not a theological dilemma at all.”

“I had faith,” said Sacks, “full stop.”

Believing in G-d is not knowing what is going to happen, but believing anyway. Belief in G-d is fumbling in the darkness, but convinced there is a light ahead. A message from this week’s Parsha that resonates so clearly the morning after Rabbi Sacks’ passing. May his soul be forever blessed.